Article | 3 November 2023

The Protective Security Act – Obligations for operators of security-sensitive activities

The interest of foreign actors to invest in the EU has long been high. Such investments have been made both by private and state-owned players and often involve the acquisition of certain influences in the target companies. Sweden, too, has long been an attractive destination for foreign investors, in large part thanks to its consistent pro-free trade agenda. In 2022, Sweden reached its highest level of investor interest to date, setting a record for inbound foreign direct investments of SEK 512 billion (approximately EUR 44 billion). The figure represents almost a threefold increase from the previous year. Foreign assets in Sweden are distributed between the service sector (66 per cent) and the manufacturing industry (34 per cent).

There are many proven advantages with foreign direct investments. However, as the awareness around foreign investors acquiring decisive ownership stakes in the EU has grown, so have concerns about the need to protect various national interests. The political discourse on national protective needs saw a significant increase in the EU during the COVID-19 pandemic. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and the economic volatility resulting from Western sanctions against Russia, further fuelled the already high-profile issue of national resilience and autonomy.

In 2023, the Swedish Security Service assessed that the security situation in Europe had seriously deteriorated during 2022. In addition to the tensions between Russia and the West, China’s and Iran’s systematic espionage and technology acquisition are mentioned as particular reasons. This deterioration has had a direct negative impact on Sweden.

The tense global geopolitical and economic situation has led many countries to introduce new or amended regulations to strengthen the protection of national security interests. In this series of articles, Setterwalls takes an in-depth look at three key regulations for Swedish companies with activities deemed “worthy of protection”, and their implications for transactions.

This first article discusses the Swedish Protective Security Act. Part two and three will review the Swedish Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Regime and the EU’s Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) respectively.

History and ambition of the Swedish Protective Security Act

In 1996, the Swedish Protective Security Act (Sw. säkerhetsskyddslagen (2018:585), the “PSA”) entered into force in Sweden. Since then, the framework has seen several revisions and adaptations to meet the current security challenges. The latest major changes were introduced in December 2021, when the legislation was adapted, amongst other things, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The PSA applies to business operators who conduct “security-sensitive activities” (Sw. säkerhetskänslig verksamhet). This covers activities of importance to Sweden’s security or that are covered by an international protective security commitment binding to Sweden.

The PSA does not exhaustively list what activities are considered security-sensitive in Sweden. The risk of having a publicly available list of activities deemed protection-worthy (Sw. skyddsvärd) has been considered too great. Guidance must instead be sought in the preparatory works of the PSA.

The term “Sweden’s security” refers to conditions of fundamental importance to Sweden, such as military activities, diplomatic activities, or civilian infrastructure, such as airports and energy plants. Certain “essential services” (Sw. samhällsviktig verksamhet) are also covered by ”Sweden’s security”. The preparatory works exemplify sectors such as energy supply, water supply, food supply, electronic communications, and financial services.

For the application of the PSA, however, it is not sufficient that an activity is simply an essential service. The decisive factor is whether such an activity can also affect Sweden’s security. This assessment is made based on the harmful consequences that an antagonistic act against the activity could produce at national level.

An example of a national essential service in Sweden is the supply of electricity, which has both a direct and indirect role for the functioning of society. An interruption of the electricity supply could mean a direct loss of light and heat but could also have far-reaching consequences in other parts of society, such as for electronic communication and payment systems.

However, to complicate things further, activities must not necessarily be of national significance to qualify as protection-worthy under the PSA – they can also exist at regional or even local level. An example of such an activity could be a locally or regionally important supplier of drinking water, a disruption of which would affect a large number of people in the region, which could ultimately have national repercussions.

Needless to say, the question of which activities are deemed protection-worthy under the PSA is difficult. The preparatory works of the PSA confirm this, stating that the threat to Sweden’s security is a complex issue of altering nature. Society has changed since the PSA was first introduced in the 1990s. Today, activities of importance to Sweden’s security can exist in other sectors of society than only, for example, the military defence sector. The resumption of the Swedish total defence planning, however, suggests that military and civil defence still constitute key areas requiring protection.

In 2022, the Swedish Security Service identified three sectors where particular vigilance was required to counteract espionage and sabotage – energy supply, telecommunications, and transports of critical supplies. According to the authority, attacks on these sectors could, in addition to causing damage to Sweden, also cause damage to the rest of Europe. Although the Security Service is a central authority for the protection of security-sensitive activities in Sweden, it is important to point out that these sectors are not an exhaustive list of activities that are deemed protection-worthy in Sweden.

General obligations for business operators

The PSA applies to business operators who conduct “security-sensitive activities”. With being an operator come a number of obligations that must be complied with in order not to risk legal sanctions.

First of all, it should be noted that operators themselves must assess whether their activities are security-sensitive or not. Operators must themselves investigate the need for security protection in a so-called “security protection analysis” (Sw. säkerhetsskyddsanalys). The security protection analysis must be documented and kept readily available. Based on the analysis, operators must plan and implement the required security protection measures relevant to their activity. This relevance is decided by the nature and scope of the security-sensitive activity and the potential existence of classified information in the business. The security protection measures must comply with the requirements for information security, physical security, and personnel security that follow from the PSA.

Operators who assess that they do conduct security-sensitive activities must notify the supervisory authority responsible for the activity without delay. The supervisory authorities are listed in the Protective Security Regulation (Sw. säkerhetsskyddsförordningen (2021:955)), Chapter 8, Section 1. The Swedish Security Service and the Swedish Armed Forces are so-called coordination authorities that follow up, evaluate, and develop the supervisory work of the other authorities further.

Once an operator has informed the responsible authority of its security-sensitive activities, the operator must continuously monitor the security protection in the business and notify anything of importance to the supervisory authority.

Further obligations for operators of security-sensitive activities include appointing a security officer (Sw. säkerhetsskyddschef) and screening relevant staff according to applicable security clearance rules. In some cases, operators are also required to enter into specific security agreements (Sw. säkerhetsskyddsavtal) if a third-party contractor may gain access to classified information or the security-sensitive activities through a contractual relationship with the business.

Supervisory authorities may sanction operators or shareholders in security-sensitive businesses for not following their obligations under the PSA. Sanctions for private actors can span from SEK 25 000 to 50 000 000. For state authorities, municipalities and regions, the upper limit is SEK 10 000 000.

When assessing whether sanctions should be imposed, the supervisory authorities will consider the damage or vulnerability to Sweden’s security that an infringement has given rise to. Other factors that can affect the assessment are whether a violation was intentional or due to negligence, and what operators or shareholders have done to put an end to the infringement and to limit its consequences once revealed.

The general awareness in Sweden of these basic obligations for operators of security-sensitive activities remains low. For example, VA Syd, one of Sweden’s largest water and waste organisations, has been fined because it failed to notify its security-sensitive operations to the supervisory authority, and thus also missed the requirement to have an updated security protection analysis in place, to appoint a security officer, and to screen relevant staff and suppliers according to the security clearance rules.

Operators still unsure about whether the PSA applies to their activities should therefore initiate an internal analysis without delay, preferably in close cooperation with legal counsel, in order to avoid potentially high sanctions.

Obligations for business operators in case of transfers

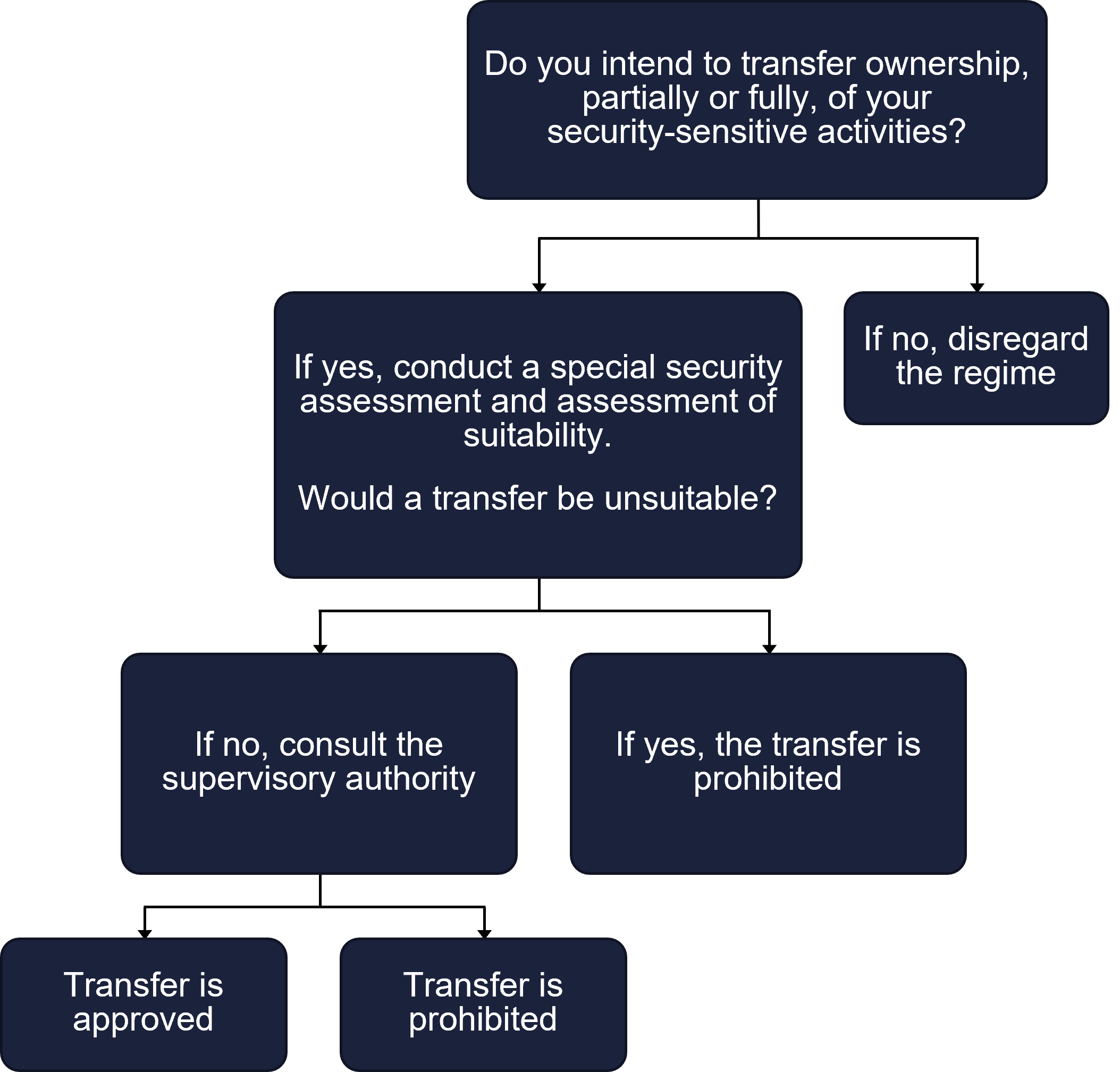

When selling security-sensitive activities, a number of additional obligations arise for business operators. Operators who intend to transfer security-sensitive activities or property, either in full or any part thereof, must prior to the transfer carry out:

- A specific security assessment and a suitability test, and

- A consultation with the responsible supervisory authority.

In the specific security assessment, the operator shall identify any classified information or other security-sensitive activities to which the acquirer may gain access through the transfer. Based on this assessment, and taking into account all other circumstances that may be of interest in the situation at hand, the operator shall then assess whether the transfer is suitable from a security point of view or not. If the suitability test leads to the assessment that the transfer is unsuitable, the transfer may not be carried out.

Where the operator assesses that a transfer would not be unsuitable, the operator shall consult the supervisory authority. The consultation stage is somewhat similar to a merger notification to the Swedish Competition Authority (“SCA”) under the Swedish Competition Act (Sw. konkurrenslagen (2008:579)). Supervisory authorities have a mandate under the PSA (similar to the SCA’s mandate under the Competition Act) to approve a transfer, impose commitments for an approval, or prohibit a transfer altogether. Authorities also have a possibility under the PSA to prohibit transactions ex post, i.e., after they have been implemented.

A notable difference compared to the Competition Act, however, is that the PSA does not set any statutory timelines for the consultation process. This ultimately means that parties wishing to transfer or acquire all or part of a security-sensitive business need to consider the notification procedure well in advance and must at an early stage consider the possible risk of a lengthy consultation process with the authority. As the consultation procedure is mandatory and suspensory, parties are not allowed to “close” a transaction until the transfer has been approved by the authority.

Transfers conducted in breach of a prohibition decision by a supervisory authority are void under civil law, meaning that such an agreement cannot be enforced. Parties to such a transfer are then not obliged to fulfil their respective commitments under the agreement, and any performances which have been made must be reversed if ordered by the supervisory authority. When notifiable transfers, which meet the conditions for prohibition according to the PSA, are carried out without consulting the relevant supervisory authority, the authority may prohibit the transfer retrospectively and declare it void. In case of void transfers, supervisory authorities may decide on such injunctions against the parties as are deemed necessary to prevent damage to Sweden’s security. Such injunctions may be accompanied by penalty payments.

Parallel application

The PSA and the Swedish FDI Regime that will enter into force on 1 December 2023 will apply in parallel to transfers of and investments in businesses with security-sensitive activities. As of 1 December 2023, there will therefore be situations when a transaction must be preceded by both a consultation procedure under the PSA and a notification procedure under the FDI Regime – to separate authorities. This may have significant impacts on deal timing considerations and contractual negotiations regarding warranties, risk allocation and ultimately purchase prices. Transactions falling under both regimes will undoubtedly require more careful planning going forward in order to avoid the possible bottlenecks.

Setterwalls comments

Setterwalls comments

The question of what business activities are considered protection-worthy in Sweden is a complex issue of altering nature. It follows from the preparatory works that Sweden’s security includes both activities of fundamental importance to Sweden, such as military activities and civilian infrastructure, as well as certain essential services, such as the secured supply of energy, water, and food.

As the general security awareness in Sweden has increased, the regulatory framework protecting Sweden’s security has tightened and the requirements for business operators have become increasingly complex. The basis for assessing which transfers to prohibit is what potentially harmful consequences an antagonistic act against the business could entail at national level in Sweden.

Our key takeaways for business operators are:

- Keep in mind that the PSA is already in force and that high sanction fees have been imposed on both private and public actors for failing to adapt their businesses accordingly.

- If your business conducts activities that risk falling under the PSA and you have not already addressed the potential need for security protection in a security protection analysis, this work should be started immediately and in close consultation with legal counsel.

- If your business is found to be security-sensitive without meeting the legal obligations for such businesses, there is a significant risk of high sanction fees. In these cases, the matter of informing the supervisory authority may become a highly tactical question, as the way this dialogue is conducted can affect the risk of possible sanctions.

Setterwalls’ lawyers have extensive experience in assisting businesses at all stages of transfers under the PSA and are used to manage the dialogue with the supervisory authorities for our clients. We therefore encourage you to reach out in case of any uncertainties regarding the applicability of the PSA or its potential impact on your future transactions. Such contact can, of course, be made on a no-names basis if desired.

A summary of this article is available for download here: The Protective Security Act in three minutes

Contact:

Practice areas: