Article | 9 November 2023

The Swedish FDI Regime – Obligations for Swedish and foreign investors

The interest of foreign actors to invest in the EU has long been high. Such investments have been made both by private and state-owned players and often involve the acquisition of certain influences in the target companies. Sweden, too, has long been an attractive destination for foreign investors, in large part thanks to its consistent pro-free trade agenda. In 2022, Sweden reached its highest level of investor interest to date, setting a record for inbound foreign direct investments of SEK 512 billion (approximately EUR 44 billion). The figure represents almost a threefold increase from the previous year. Foreign assets in Sweden are distributed between the service sector (66 per cent) and the manufacturing industry (34 per cent).

There are many proven advantages with foreign direct investments. However, as the awareness around foreign investors acquiring decisive ownership stakes in the EU has grown, so have concerns about the need to protect various national interests. The political discourse on national protective needs saw a significant increase in the EU during the COVID-19 pandemic. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and the economic volatility resulting from Western sanctions against Russia, further fuelled the already high-profile issue of national resilience and autonomy.

In 2023, the Swedish Security Service assessed that the security situation in Europe had seriously deteriorated during 2022. In addition to the tensions between Russia and the West, China’s and Iran’s systematic espionage and technology acquisition are mentioned as particular reasons. This deterioration has had a direct negative impact on Sweden.

The tense global geopolitical and economic situation has led many countries to introduce new or amended regulations to strengthen the protection of national security interests. In this series of articles, Setterwalls takes an in-depth look at three key regulations for Swedish companies with activities deemed “worthy of protection”, and their implications for transactions.

This second article discusses the upcoming Swedish FDI Regime. Part one reviewed the Swedish Protective Security Act, while part three will focus on the EU’s Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR).

A brief history of FDI screening mechanisms

The matter of foreign direct investments (“FDI“) is closely connected to politics, partly due to the fact that FDI are an important financing tool in international trade. Economists usually advocate free flow of capital across borders because it allows the companies investing the capital to seek the highest return rates which, in theory, promotes the competitiveness of countries.

There is considerable evidence that FDI benefits the countries to which capital is transferred. For smaller economies, in addition to the pure inflow of capital, FDI can also contribute to increased productivity and innovation through the exchange of knowledge and technology. For larger economies, a significant inflow of FDI can signal that the host country is an attractive business destination. Nevertheless, the positive effects of FDI should be carefully and realistically weighed against its potential drawbacks.

The EU has long had one of the world’s most open investment systems. This has led to many foreign companies and, in some instances, state-owned actors gaining influence in the EU through financial investments in EU firms. At the same time, the same investors’ countries of origin have often maintained significant investment barriers towards EU investors. Over the years, concerns over this unilateral trade exchange have grown in the EU.

Interest in FDI skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic when the European industry was under great financial pressure. Many EU Member States – some more than others – suddenly saw an immense need to prevent foreign acquisitions of strategic national and European assets, arguing that these acquisitions could threaten security or public order in the EU if carelessly allowed. The solution for many was to introduce or extend existing rules for screening foreign investments.

The political pressure that was exerted on the legislative discussions regarding FDI regimes during the pandemic was somewhat reminiscent of the political lobbying which took place in the EU in the 2010’s. During this earlier period, the focus lay on the European industry’s resilience and position on the world market. The discussions subsided after 2019 when the European Commission, to the great disappointment of Germany and France, blocked the merger between Siemens and Alstom, which would have created what some called Europe’s first “Champion”. The discussions on the importance of FDI screening were, however, conducted from a different starting point, namely that Europe needed to be protected from the external threat of state-owned foreign investors.

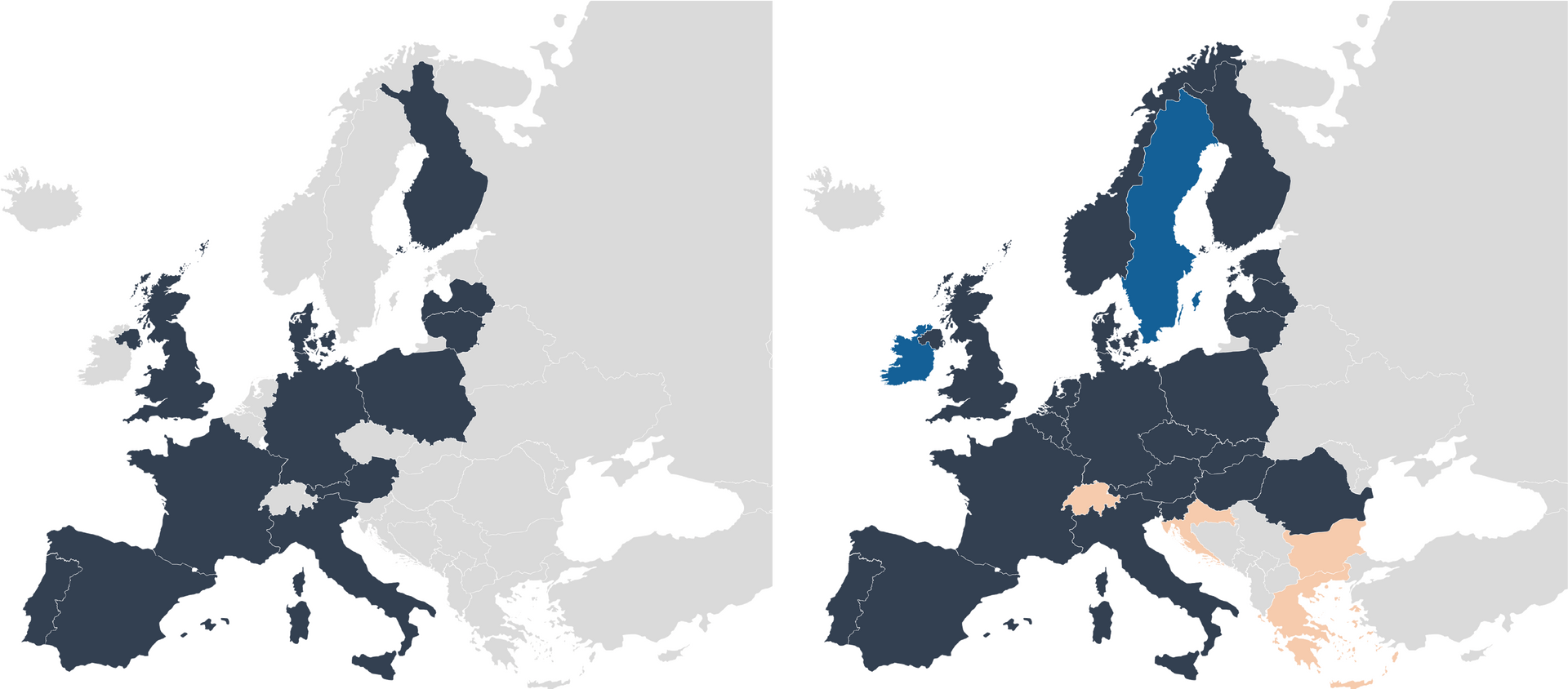

In 2019, the EU FDI Regulation (2019/452) was published, establishing a legal framework for the screening of FDI in the EU. The Regulation, which applies since 11 October 2020, allowed EU Member States to design their own national screening systems to protect national security and public order. Many Member States acted quickly, and by the end of 2023, it is expected that 23 EU Member States will have implemented FDI screening mechanisms in one form or another, compared to 12 Member States in 2017.[1]

2017 2023

Dark blue indicates jurisdictions with an FDI regulation. Light blue indicates jurisdictions where regulations are expected to be introduced shortly. Orange indicates jurisdictions where legislative work towards an introduction has been initiated.

In short, these screening mechanisms allow national authorities to control which foreign investments are allowed. Authorities generally have the right to restrict or prohibit investments when necessary in order to protect national security. Thereby, countries can avoid the possible risks of foreign investments in certain sectors which are deemed protection-worthy.

The screening of FDI is inherently a national issue, not at least as national security interests may differ between countries. Each Member State in the EU has the possibility to establish its own screening mechanism and to decide which sectors are most critical to protect.

The Swedish FDI Regime

Presently, Sweden does not yet have a comprehensive regulatory framework that enables authorities to prevent potentially harmful investments in Swedish companies that require protection. However, such a regime will enter into force on 1 December 2023 (the “FDI Regime“). Sweden is one of the last EU Member States to introduce such a mechanism.

The FDI Regime, as currently drafted, aims to prevent FDI in Swedish businesses conducting “activities requiring protection”, when an investment could be to the detriment of Sweden’s security, public order, or public safety in Sweden.

The draft Regime defines “foreign direct investments” as investments made by natural persons with citizenship or legal entities established in a non-EU state. Additionally, investments are considered foreign when made by legal entities that are directly or indirectly owned or controlled by a non-EU state. The same goes for legal entities which are owned or controlled by a legal entity established in, or a natural person with the nationality of, a non-EU state.

The FDI Regime aims to control investments that establish or maintain lasting relations between the investor and the company for which the capital is made available. This includes any investment that enables effective participation in the management or influence of a company engaged in economic activities that require protection.

When such investments exceed certain percentage thresholds, they will need to be notified to the supervisory authority (see more below under the heading “Obligations for investors and business operators”). Effectively, this means that an investment in a parent company with a Sweden-based subsidiary that conducts activities requiring protection may need to be notified.

The FDI Regime is intended to apply to the most common company forms with a registered office in Sweden, i.e., limited liability companies (Sw. aktiebolag), European companies (Sw. europabolag), trading partnerships (Sw. handelsbolag), simple partnerships (Sw. enkla bolag), economic associations (Sw. ekonomiska föreningar), foundations (Sw. stiftelser), and sole traders (Sw. enskild näringsverksamhet).

Activities requiring protection in Sweden

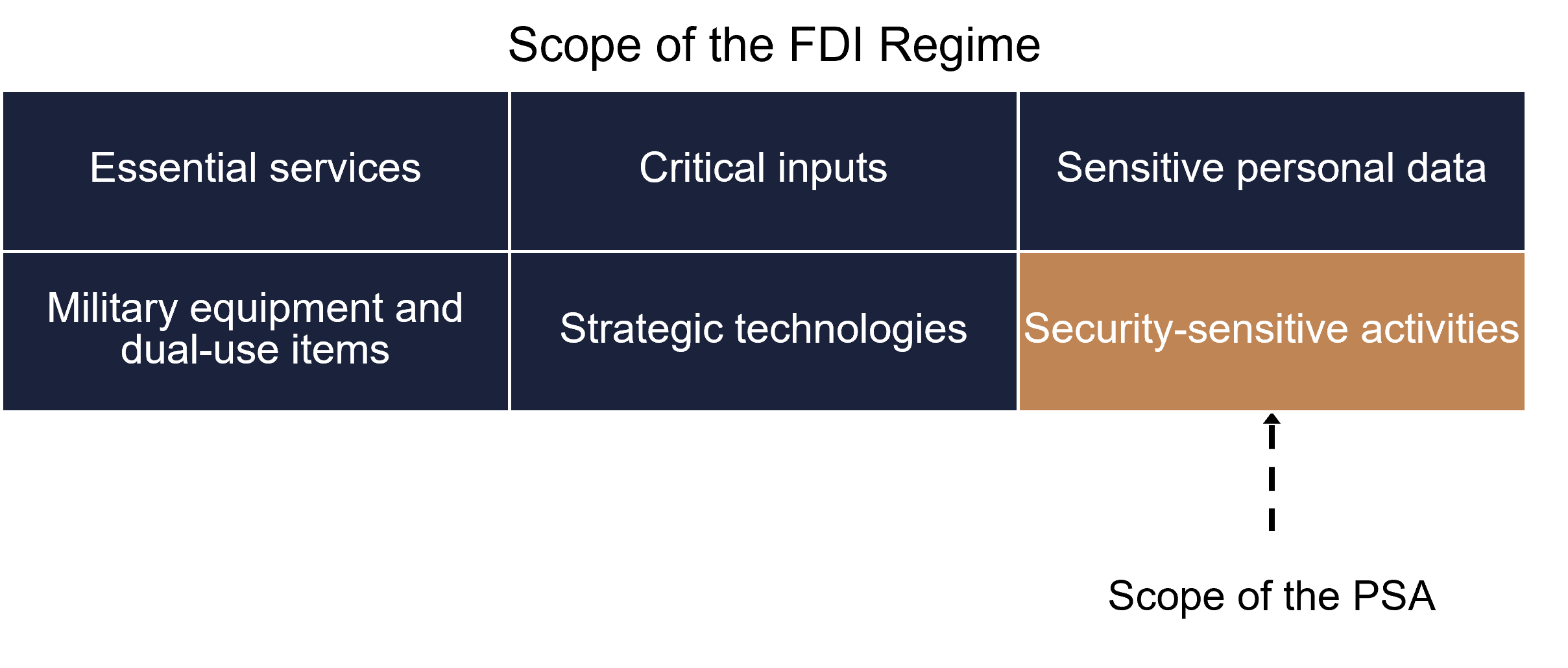

The FDI Regime list the following activities as requiring protection in Sweden:

Essential services (Sw. samhällsviktig verksamhet)

The FDI Regime will apply to investments in companies that conduct essential services. Essential services are defined as activities, services or infrastructure that maintain or ensure essential functions for the basic needs, values or security of society in Sweden.

The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (the “MSB“) has drafted implementing regulations specifying this further. The authority’s proposal, which at the time of this article being published is still out for consultation and may therefore be adapted, considers the following activities to be essential services in Sweden:

- Extraction of minerals

- Manufacturing

- Supply of electricity, gas, heating, and cooling

- Water supply, wastewater treatment, waste management, and sanitation

- Construction activities

- Trade

- Transport and storage

- Hotel and restaurant activities

- Information and communication activities

- Financial and insurance activities

- Real estate activities

- Activities in law, economics, science, and technology

- Rental, real estate, travel, and other support services

- Education

- Health care, social care, and social services

The MSB estimates that about 1.3 million companies may be covered by this initial frame. The authority plans to exempt approximately 1.2 million companies which have fewer than 5 employees. Nonetheless, if the implementing regulations remain as broad as they are now, there remain just over 100 000 companies that could be considered essential services under the FDI Regime.

The draft implementing regulations contain a general limitation, excluding companies with a turnover below SEK 5 million. Some activities have a higher turnover threshold, while others are planned to have no such thresholds at all, meaning that investments in these sectors will have no safe harbour at all. Activities with a higher turnover threshold include the production, processing, and trade of food.

Security-sensitive activities (Sw. säkerhetskänslig verksamhet)

The FDI Regime will apply to investments in companies that conduct security-sensitive activities according to the Swedish Protective Security Act (Sw. säkerhetsskyddslagen (2018:585), the “PSA”). Which activities are deemed protection-worthy under the PSA is a complex issue of altering nature. It follows from the preparatory works that the object of protection under the PSA – “Sweden’s security” – includes both activities of fundamental importance to Sweden, such as military activities and civilian infrastructure, as well as certain essential services, such as the secured supply of energy, water, and food.

The FDI Regime and the PSA will thus have a partly overlapping scope of application. Both regulations cover security-sensitive activities and, to varying degrees, essential services. However, the scope of the PSA is limited to activities that are important for “Sweden’s security”. The scope of the FDI Regime is broader, also covering activities of importance for “public order” and “public security” in Sweden.

This overlap will have obvious consequences for some business operators and investors, as the regulations will need to be applied in parallel for certain transfers of and investments in security-sensitive activities (see more below under the heading “Parallel application“).

The MSB does not indicate on what grounds it has selected the essential services listed in its implementing regulation. Consequently, it is not possible to draw any conclusions as to which essential services fall under the narrower scope of the PSA. The assessment of supervisory authorities under the PSA will therefore ultimately be based on what potentially harmful consequences an antagonistic act against the business could entail at national level in Sweden.

Activities involving critical raw materials or other critical inputs (Sw. kritiska råvaror eller andra kritiska insatsvaror)

The FDI Regime will apply to investments in companies that explore, extract, enrich, or sell raw materials critical to the EU, or other metals and minerals critical to Sweden’s supply. The Government’s list of critical raw materials and inputs includes, inter alia, iron, limestone, and copper. The list is available in full in Annex 1 of the ordinance on foreign direct investment screening (SFS 2023:624).

Activities processing sensitive personal data and location data (Sw. känsliga personuppgifter och lokaliseringsuppgifter)

The FDI Regime will apply to investments in businesses that extensively process sensitive personal data under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679) or location data under the Swedish Electronic Communications Act (Sw. lagen om elektronisk kommunikation (2022:482)). For the purposes of these activities, processing means, inter alia, the collection, recording, storing, and processing of such data.

In the assessment of what constitutes “extensive” processing, the supervisory authority shall take particular account of the number of data subjects concerned, the amount of data, and what types of data is processed. The assessment shall also consider the length or duration of the processing, as well as the geographical scope of the processing. An example of large-scale processing according to the preparatory works of the FDI Regime is the processing made by telephone or internet service providers regarding location data of the connected telephones or computers.

Activities relating to military equipment and dual-use items (Sw. krigsmateriel och produkter med dubbla användningsområden)

The FDI Regime will apply to investments in businesses that manufacture, develop, research, or provide military equipment as defined in the Military Equipment Act (Sw. lagen om krigsmateriel (1992:1300)) or provide technical assistance for such military equipment.

The FDI Regime will also apply to investments in businesses that manufacture, develop, research, or provide dual-use items under the EU Dual-Use Regulation (2021/821) or provide technical assistance for such items.

Activities relating to emerging and other strategic technologies that require protection (Sw. framväxande teknologier och annan strategiskt skyddsvärd teknologi)

The FDI Regime will apply to investments in businesses that research or supply products or methods relating to emerging technologies or other strategic technologies that require protection. The same goes for businesses with activities that are capable of manufacturing or developing such products or methods.

The Inspectorate for Strategic Products (the “ISP”) has drafted implementing regulations, similar to the MSB for “essential services”, which specify emerging technologies and other strategic technologies requiring protection. According to the proposal, the following technologies are deemed to require protection:

- Nuclear materials, facilities, and equipment

- Specific materials and related equipment

- Material processing

- Electronics

- Navigation and avionics

- Flight, space, and propulsion

- Other AI algorithms and military machine learning algorithms

Obligations for investors and business operators

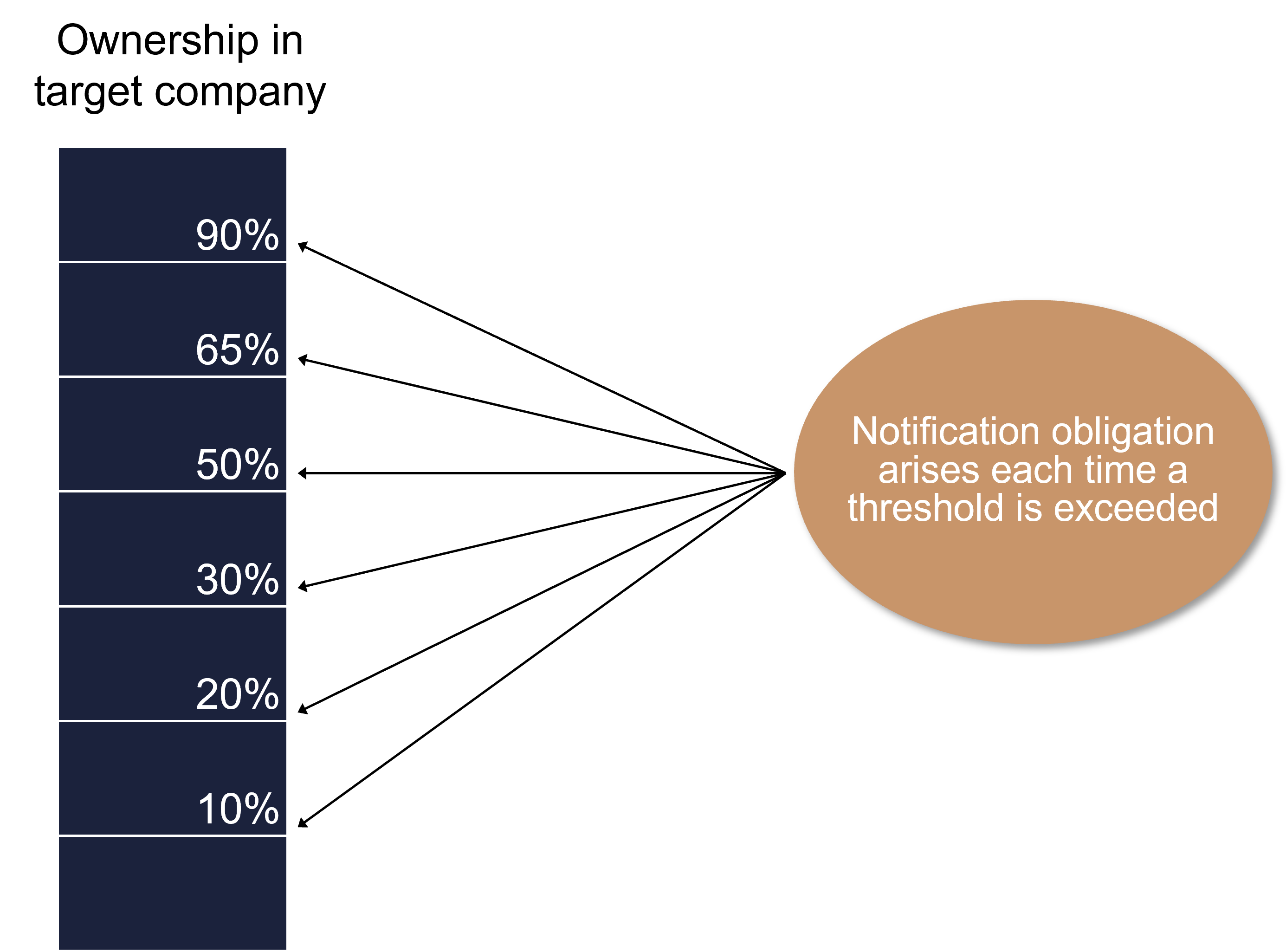

From 1 December 2023, direct and indirect investments in businesses falling under the FDI Regime will, under certain circumstances, need to be notified to the ISP prior to the investment being made. Notifications must be made if the investor, a member of the investor’s ownership structure, or someone on whose behalf the investor is acting, after the investment exceeds any of the voting rights thresholds in the target company. The thresholds are 10, 20, 30, 50, 65 or 90 per cent. The ISP can also initiate reviews on its own initiative in situations when a filing is not triggered.

An investment must also be notified if it would otherwise grant the investor the possibility to exert direct or indirect influence on the management of the target company. Generally, it is the legal or natural person carrying out the transaction that is responsible to notify.

This means that consecutive investments in the same target company need to be notified to the ISP every time a threshold is exceeded. An exception is made for the acquisition of shares in a new share issue, when the shares are acquired with preferential rights in relation to the number of shares the investor already owns.

The FDI Regime will cover both “greenfield investments”, i.e., investments in new operations, and “brownfield investments”, i.e. investments in existing operations. Thus, it appears that the Regime will cover investments in both newly formed companies and shelf companies if such a company is to carry out activities requiring protection. It is difficult to say how this assessment will be done in practice. Until this is clarified further, investors and project developers wanting to invest in the early stages of projects that may fall under the FDI Regime once taken into operation are left with no guidance whether to notify investments or not.

Business operators with activities falling under the FDI Regime must inform potential investors of the applicability of the Regime. In case an investment exceeds the notification thresholds, the Regime will thus entail a disclosure obligation for the business operator towards the investor, and a notification obligation for the investor towards the ISP.

The notification process

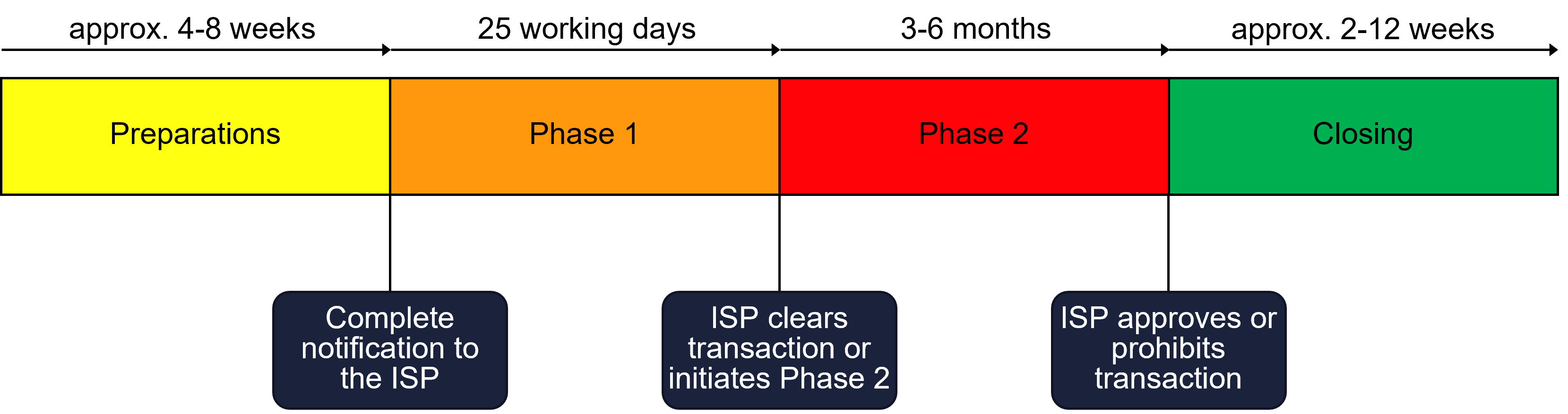

The notification process to the ISP is designed as a two-step procedure and will largely mirror the process for merger notifications to the Swedish Competition Authority under the Swedish Competition Act (Sw. konkurrenslagen (2008:579)).

Within 25 working days from receiving a complete notification (“Phase 1“), the ISP must decide either to leave an investment without action or to initiate an in-depth review (“Phase 2“). If the ISP initiates Phase 2, the authority must decide whether to approve an investment, if necessary subject to commitments, or prohibit it within three months. In specific cases, this timeframe can be extended to six months.

Any investment in a business covered by the FDI Regime that exceeds the voting rights thresholds will need to be notified to the ISP. This also includes purely domestic investments, i.e., investments by Swedish citizens initiated on their own account. According to the preparatory works, the same ought to apply to investments by legal entities that are owned or controlled solely by natural persons with only Swedish citizenship, and that do not act for the benefit of anyone else. The same assessment should also be made regarding natural persons who are only citizens of other EU Member States.

The rationale for not exempting Swedish investors from the notification obligation is that such investors could otherwise act as fronts for foreign investors with interests detrimental to Sweden’s security. While the aim is noble and possibly inevitable, it is also a noteworthy burden for Swedish investors.

The legislator has anticipated that the majority of notifications under the FDI Regime will be domestic or intra-European, and thus sorted out in Phase 1. The ISP will also be able to sort out notifications from investors outside the EU in Phase 1 if it is clear that the investment is not associated with any risks. However, the assessment of which notifications can be closed in Phase 1 without a more detailed investigation measures will always depend on the circumstances of the individual case, and Swedish citizenship or ownership alone is therefore no guarantee of success.

The legislator has chosen not to introduce any specific provisions on what documentation will be requested by the ISP in a notification. It is therefore not yet clear what will be required of investors and how burdensome a notification will be. There will be no possibility to receive a preliminary decision.

Sanctions

The FDI Regime will apply to transactions that “close” as of 1 December 2023. Notifiable investments closing on or after 1 December cannot be completed until cleared or approved by the ISP.

Failure to comply with the regulatory obligations can be very costly. The ISP has a mandate to impose fines of up to SEK 100 million, approximately EUR 9 million. Further, the ISP can under certain circumstances reverse transactions that should have been notified but were not. This, however, does not apply to acquisitions on certain regulated markets under the Swedish Securities Act (Sw. lagen om värdepappersmarknaden (2007:528)).

Parallel application

The FDI Regime and the PSA will apply in parallel to transfers of and investments in businesses with security-sensitive activities. As of 1 December 2023, there will therefore be situations when a transaction must be preceded by both a consultation procedure under the PSA and a notification procedure under the FDI Regime – to separate authorities.

As noted above, the scope of the PSA is narrower than the FDI Regime. Regardless, this overlap may have significant impacts on deal timing considerations and contractual negotiations regarding warranties, risk allocation and ultimately purchase prices. Transactions falling under both regimes will undoubtedly require more careful planning going forward in order to avoid the possible bottlenecks.

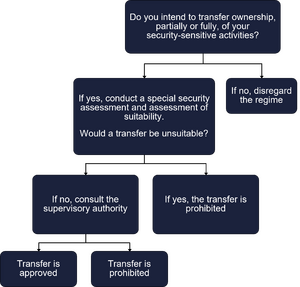

The PSA entered into force in Sweden in 1996. Since then, the framework has seen several revisions and adaptations to meet the current security challenges. The latest major changes were introduced in December 2021, when the legislation was adapted, amongst other things, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since these changes, operators who intend to transfer security-sensitive activities or property, either in full or any part thereof, must prior to the transfer carry out:

- A specific security assessment and a suitability test, and

- A consultation with the responsible supervisory authority.

Supervisory authorities can restrict or prohibit transfers that would be unsuitable from a security point of view.

Setterwalls comments

The Swedish FDI Regime will shortly be introduced. The proposed Regime is both broad (10 per cent of the voting rights in a company is a low threshold) and vague (which activities are actually covered?). Until the FDI Regime has entered into force and the contrary has been proven, it is therefore difficult to draw any other conclusion than that the Regime risks applying to a large number of transactions, and thereby become relevant to many investors and business operators in Sweden.

To substantiate this claim, a further reference can be made to the Swedish Competition Act, which generally requires that acquisitions are notified when the joint turnover of the acquirer and the target company in Sweden exceeds SEK 1 billion, and both companies had a turnover in Sweden exceeding SEK 200 million the previous year. It is obvious that a threshold of 10 per cent of the voting rights in a company – practically irrespective of the size of the target company[2] – will be exceeded far more often than the thresholds of the Competition Act.

Furthermore, this is the first time that the ISP has a transaction control assignment of this magnitude. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the authority, at least initially, may face certain challenges. One such challenge appears to be the risk of the ISP being flooded with notifications from 1 December 2023. In the absence of more precise guidance, many legal advisers are likely to adopt a cautious approach when advising clients whose activities may fall under the FDI Regime. And when clients are advised to notify investments just to be on the “safe side”, there is a risk that many unnecessary notifications are made.

Parties to transactions with a Swedish element that may trigger the application of the FDI Regime will have to consider this uncertainty in the future. On the one hand, companies risk high sanctions if the regulation is wrongly dismissed and disregarded. On the other hand, a notification to the ISP triggers a suspensory timeline of 25 working days during which a transaction may not be closed. Admittedly, the legislator has presupposed that the majority of notifications will be non-problematic transactions, which will be left without action in Phase 1. However, should the ISP initiate Phase 2, transaction timelines may receive drastic extensions which could completely disrupt existing time schedules. Few transactions can survive an unexpected delay of 3-6 months.

It is therefore not an understatement to say that investments in Swedish companies conducting activities requiring protection will become more complex in the future. This complexity will especially affect investors from outside the EU, where the risk of Phase 2 is greater. However, the complexity will also, to some extent, affect Swedish and EU investors, not to mention Swedish business operators covered by the Regime.

Investments may take longer to complete due to the mandatory notification process and possible preparatory work leading up to a notification. For parties to a transaction, this may in some cases result in indirect costs or reduced revenues, especially where delays occur. The Regime may also lead to increased transaction costs for business operators who intend to divest or raise additional capital in a business requiring protection. Indirect costs may also arise if the ISP decides to prohibit an investment ex post by ordering the parties’ respective performances to be reversed.

A more general difficulty of the Swedish FDI Regime is that it adds to the complexity of international deals involving target companies requiring FDI protection. As the screening of FDI is inherently a national issue, so is deciding which activities require protection. The legal landscape regarding FDI screening is already very complex due to the fact that objects of protection, notification processes, and timelines differ between jurisdictions. With Sweden introducing its screening mechanism, investors need to consider yet another framework, which makes it even harder to maintain an international overview.

This is further complicated by the fact that the decisions of national supervisory authorities to allow or prohibit individual investments are practically always confidential. The lack of transparency in the decision-making process makes it very difficult for investors seeking to obtain an understanding of the relevant national case law. Beyond the headlines that a transaction has been prohibited, it is often almost impossible to understand the grounds on which a supervisory authority has decided to prohibit an investment.

In Denmark, for example, the Japanese investor Hamamatsu Photonics K.K. was recently prohibited from acquiring, via its Belgium-based subsidiary, the Danish fibre laser manufacturer NKT Photonics A/S. According to the investor, the Danish prohibition followed regulatory approvals in Germany, the U.K., and the U.S. The Danish decision puzzled many business lawyers in Denmark, not least because Japan traditionally has been seen as an ally from a Danish geopolitical perspective. It remains to be seen whether Denmark’s geographical proximity to Sweden will affect the ISP’s assessment of Japanese investors.

There are thus many uncertainties. What is certain, however, is that investors and business operators of activities requiring protection in Sweden need to be prepared to deal with these issues. For this, a strong partner with both legal expertise and a finger on the pulse of political developments is invaluable.

Setterwalls’ lawyers already have solid experience of working with FDI screening mechanisms from other jurisdictions around the world and are therefore well prepared for the upcoming Swedish Regime. We therefore encourage you to reach out in case of any uncertainties regarding the applicability of the Regime or its potential impact on your transactions. Such contact can, of course, be made on a no-names basis if desired.

For investors:

- Does the company you intend to invest in carry out activities requiring protection?

- If yes, does the proposed investment exceed any of the regulatory thresholds?

- If yes, engage with the target company and complete a notification to the ISP.

- Be particularly careful in transactions involving more than one jurisdiction, as multiple FDI filings could be triggered.

For business operators:

- Does your company carry out activities requiring protection?

- If yes, initiate a dialog with the ISP to ensure that you meet all obligations under the FDI Regime, such as informing potential investors of the applicability of the act.

A summary of this article is available for download here: The FDI Regime in three minutes.

[1] By the end of 2023, Croatia, Greece, Cyprus, and Bulgaria stand without a corresponding regulatory framework, but legislative work has been commenced. Ireland published draft legislation in 2022 to introduce a new FDI screening mechanism. The proposal is currently being considered by its Parliament and expected to come into force early 2024. In Switzerland, legislative work is underway to introduce an FDI framework. Norway is included in the 2023 list for information purposes only. Both Norway and Switzerland are, as EEA member states, considered as third states under the Swedish FDI Regime. The UK left the EU on February 1, 2020, but remains in the 2023 list for information purposes. The Swedish Protective Security Act, which has been in force in Sweden since the 1990s, has not provided a comprehensive review system, which is why Sweden lacks a FDI regime in the 2017 graphic.

[2] It remains to be confirmed that the FDI Regime entirely lacks a turnover requirement for target companies. Currently, the MSB has, in its implementing regulation for essential services, proposed a general turnover requirement of SEK 5 million for the majority of these activities, although there are exceptions in both directions.

Contact:

Practice areas: